01 December 2022

P.R. Jenkins

Spotlight Bruckner: Your guide to the symphonies

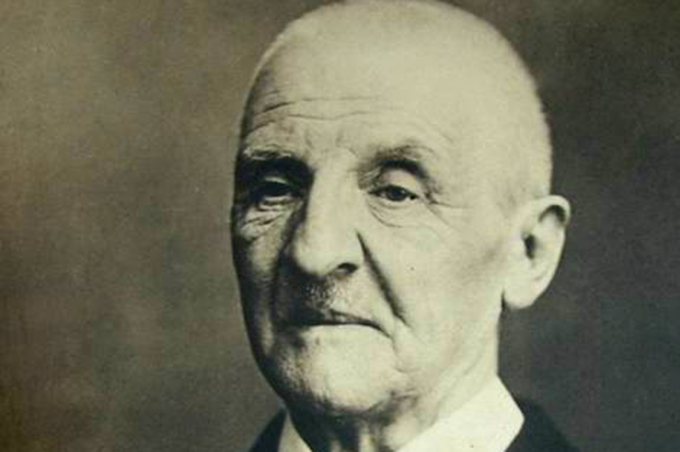

In this episode of the Spotlight series we are looking at Karajan’s interpretations of the Bruckner symphonies. As was the case with many other great 20th-century conductors, Bruckner’s oeuvre was a central pillar in Karajan’s symphonic repertoire. In his last season 1988/89, he chose two Bruckner symphonies for his last performance in New York (the 8th) and for his last concert of all in Vienna (the 7th). Whereas some of the symphonies like the 8th were on Karajan’s programmes from the very beginning to the end of his career, he only recorded the early ones in the studio and never performed them live.

We’ve prepared playlists for you with Bruckner’s orchestral works. Listen to them here.

Symphony No. 1

Beethoven wrote his first symphony at the age of 29, Dvořák was 24, Schubert was16. Bruckner’s symphony in C minor is not the work of a young man. He was 42 when he wrote the first work he thought worthy of performing (after a Study Symphony in F minor called “No. 00” and before the “No. 0” in D minor) in a genre in which he is today looked on as a giant. In the first symphony everything is already there – the mysterious Bruckner “sfumato”, the characteristic main theme in the first movement, the epic calm of the adagio, the uncompromising scherzo and the triumphant finale. Bruckner – who called this symphony “das kecke Beserl” (“the saucy minx”) – conducted its first performance in 1868 and later revised it several times. Karajan recorded the so-called “Linz version”, which in fact was made in Vienna in 1877 and edited by Leopold Nowak in 1953.

Karajan’s only interpretation of Bruckner’s symphony No. 1 with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1981 was described by Karajan biographer Richard Osborne as a recording of “electrifying intensity”.

Symphony No. 2

Bruckner’s symphony No. 2, which like No. 1 (and No. 8) is in C minor, was actually his fourth, and like all the others it was revised several times. It was completed in 1872 and the first performance in the same year with the Vienna Philharmonic under Otto Dessoff was planned and rehearsed but did not in fact take place. Bruckner himself conducted the premiere with the Vienna Philharmonic in the following year during the “Vienna World Fair”. As Franz Liszt did not respond to Bruckner’s dedication, No. 2 is the only one of his symphonies without a dedicatee.

Karajan’s only interpretation is the 1981 studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic for which he uses Leopold Nowak’s edition of Bruckner’s 1877 version.

Symphony No. 3

Bruckner’s symphony No. 3 in D minor was written in 1872/73 and completed on 31 December 1873 “at night”. (Finishing a major symphony – quite a good way to spend New Year’s Eve!) At an earlier stage of the composition, Bruckner had called it “A Wagner Symphony” and quoted motifs from “Tristan”, “Meistersinger” and “The Ring” so it’s no surprise that Wagner is the dedicatee of this piece. Bruckner visited him in 1873 and offered him No. 2 or No. 3. Wagner took No. 3 but – according to an anecdote – the two men spent the evening drinking beer and the next day Bruckner couldn’t remember Wagner’s decision. He had to write him a letter and ask again… The first performance in 1877 was ill-fated, as the conductor Johann Herbeck died a month before the concert and Bruckner (not a well-versed conductor) had to lead the Vienna Philharmonic himself. It was a disaster, the audience left during the symphony. But there were also supporters like Gustav Mahler, who made a four-hand version at the age of 20 and was given a part of one of the autographs by Bruckner. The work is Bruckner at his best and it is not easily understandable that it is less often to be sound on concert programmes than the later symphonies.

Karajan used Bruckner’s last version of 1889 edited by Leopold Nowak for his only studio recording in1980. He never performed it live.

Symphony No. 4

This symphony is maybe the most popular work in Bruckner’s oeuvre – No. 4, the “Romantic”, written in 1874. Starting with the successful first performance by the Vienna Philharmonic under Hans Richter in 1881, the Fourth – his first symphony written in a major key – has kept its place in the symphonic repertoire. Although it has no “programme” like the symphonic poems of Berlioz and Liszt, Bruckner confided some of his associations to his friends. The beginning, he says, is reminiscent of “a mediaeval city – daybreak – morning calls sound from the city towers – the gates open – on prancing steeds the knights sally forth – the magic of nature envelops them – forest murmurs, bird song – and so the romantic picture develops further.” The third lyrical theme (“Gesangsperiode”) recalls the song of the great tit.

Unlike the first three Bruckner symphonies, Karajan’s engagement with the Fourth dates all the way back to the very first steps he took as a conductor, as he wrote to his parents in 1927. His first public performance of the “Romantic” was in Aachen in 1936 and it is quite surprising that he waited till 1970 to commit it to disc as “a glowing essay in the pastoral style” (Richard Osborne). A second version from 1975 – again a studio production with the Berlin Philharmonic – is more than 5 minutes faster.

Symphony No. 5

Bruckner considered the fifth symphony to be his “contrapuntal masterwork” and it is arguably his most enigmatic and complex work but also the one with “the most monumental finale in the whole symphonic literature” (Wilhelm Furtwängler). It was written between 1875 and 1878 and was played (and praised) shortly after its completion by Franz Liszt, who visited Vienna in 1878, presumably from the hand-written score. The symphony was presented to the public for the first time in a version for two pianos in Vienna in 1887. The first performance with orchestra took place in Graz under the baton of Bruckner’s pupil Franz Schalk in 1894. This was two years before his death, and Bruckner was already too ill to attend – in fact he never heard this symphony played by an orchestra. Schalk revised Bruckner’s orchestration to make it sound more “Wagnerian” and cut out about 15 – 20 minutes of music. The first performance of the Fifth in its original form came as late as 1935, in Munich.

Karajan valued the demanding piece and performed it more often than the popular “Romantic”, 32 times between 1937 and 1981. There aren’t many Bruckner recordings by Karajan from the 1950s but the 1954 live recording with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra is an interesting alternative to his 1976 studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Symphony No. 6

Unlike many other Bruckner symphonies, the Sixth exists in one single version. Bruckner seemed to have been exceptionally happy with and he joked: „Die Sechste – die keckste“ (“the Sixth – the sauciest”). It was written between 1879 and 1881, the second and third movements were first performed by the Vienna Philharmonic in 1883. In 1899, three years after Bruckner’s death, it was Gustav Mahler who conducted the first “complete” performance, again with the Vienna Philharmonic. Mahler presented the Sixth in a shortened version and with revisions to the orchestration. The whole work was first performed without cuts in Stuttgart in 1901. It is a wonderful piece, powerful and cogent, with one of Bruckner’s most beautiful slow movements, and it is hard to understand why it is less often performed than the late symphonies.

Karajan conducted the Sixth only once for his studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1979. He never performed it live.

Symphony No. 7

“Zum Andenken an den Hochseligen, heißgeliebten unsterblichen Meister (To the memory of the highly blessed, beloved immortal master)”

Anton Bruckner

On 8 December 1881, one of the most terrible fire disasters in the history of Austria took place in Vienna, the “Ringtheaterbrand”. The Ringtheater was a theatre for “light” opera and operetta and stood right next to the house where Bruckner was living at that time. Bruckner actually had a ticket for the performance of “The Tales of Hoffmann” that evening but decided to stay at home because he wasn’t well. If he’d attended the performance he would hardly have survived, for hundreds of people were killed. Bruckner witnessed the catastrophe from his windows and it may have inspired him to write the gloomy scherzo of the Seventh. The famous adagio – one of the most impressive slow movements in the symphonic literature – was also planned as a lament for the dead. Later it was used as the funeral music for Richard Wagner, whose death on 13 February 1883 Bruckner had already anticipated when he wrote to the conductor Felix Mottl a few weeks earlier: “I came home and was very sad. I thought, the master won’t live much longer. That’s when the adagio in C sharp minor came to my mind.” The first performance with orchestra in 1884 – significantly not in Vienna but in Leipzig – was the greatest success in Bruckner’s life. He was already 60 at the time. Up to the present day, the Seventh (together with the Fourth) has been his best-loved work.

Karajan regularly conducted the Seventh over a period of 48 years and it is a well-known fact that this piece was the last he conducted in public in April 1989. In 1974, 150 years after Bruckner’s birth, Karajan conducted the Seventh with the Vienna Philharmonic at the grand opening of the new “Brucknerhaus” concert-hall in Linz, near Bruckner’s birthplace Ansfelden. Karajan’s first studio recording of the Seventh with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1970 was described as “arguably the most purely beautiful account of the symphony there has ever been on record.” (The Gramophone)

Symphony No. 8

Bruckner’s Eighth is his last complete symphony and the longest of them all. Written in a complicated process between 1884 and 1890, it was refused by Wagner-conductor Hermann Levi in 1887, then revised and first performed by Hans Richter and the Vienna Philharmonic in 1892 – with tremendous success. The whole symphony is the crown jewel in Bruckner’s oeuvre, a mystical journey with previously unheard-of modulations and formal experiments. Today, “Bruckner’s Eighth” has remained a synonym for the most important and impressive works in the orchestral repertoire.

The Eighth is the Bruckner symphony Karajan performed and recorded most often between 1937 in Aachen and his last New York concerts in February 1989. The New York performance with the Vienna Philharmonic – five months before his death – was a sensation. Richard Osborne reports: “Sitting, drained and physically diminished, after the Bruckner (…) he marvelled at what he had heard. ‘That was not me,’ he told Ronald Wilford. ‘I don’t know who or what it was, but it was not me.’” Osborne also considers: “Karajan’s skill was that he could cast an eighty-minute Bruckner symphony as a single piece. His ability to sustain and where necessary re-engage a basic pulse was second to none.”

Symphony No. 9

Bruckner’s Ninth, his last symphony, remained unfinished. Movements 1, 2 and 3 were completed, but although Bruckner worked on it to his very last days, he wasn’t able to finish the finale. Like many other fragmentary last works by Bach, Mozart or Mahler, the Ninth caused speculations about Bruckner’s intentions for the entire symphony. Apparently, Hans Richter suggested replacing the incomplete finale with the “Te Deum” and Bruckner began to compose a transition for this solution. Despite several attempts by musicologists and composers to complete it, the Ninth is performed and recorded most often in its three-movement form. And there are theories that this (unintended) form inspired subsequent composers like Mahler to end symphonies with a slow movement. On 11 October 1896 Bruckner died in Vienna. Bernhard Paumgartner, Karajan’s mentor and president of the Salzburg Festival, attended Bruckner’s funeral service as a child and reported later that a man who had always been seen as Bruckner’s opponent hid behind a column and left the church earlier with tears in his beard – Johannes Brahms.

Karajan conducted Bruckner’s Ninth 38 times between 1938 in Aachen and 1986 in Berlin. Gramophone wrote in 1997: “For loftiness of aim and a long-lined symphonic reach, it is difficult to imagine the various Karajan recordings being surpassed”.

The Ninth seemed to be remarkably appropriate for memorial concerts after Karajan’s death. The Berlin Philharmonic Karajan memorial concert on 10 September 1989 featured it with Carlo Maria Giulini and it was also performed by Seiji Ozawa in a concert with the Vienna Philharmonic marking the 10th anniversary of his death in Salzburg in 1999.

Te Deum

“Yesterday (Good Friday) I conducted your marvellous and tremendous ‘Te Deum’. (…) At the end of the performance I witnessed what I think is the greatest success a piece can have: The audience sat there speechless and motionless. Only when the conductor and the participating artists started leaving did thunderous applause burst out.”

Gustav Mahler to Anton Bruckner in a letter from Hamburg in 1892

Bruckner’s “Te Deum” is one of his mature works for orchestra, chorus and vocal soloists. The text is an early Christian hymn which is not part of the liturgy but is used for high festivities in church. Bruckner wrote the “Te Deum” between 1881 and 1884, neither as a commissioned work nor for any special occasion, but “as a token of thanks that my enemies haven’t managed to get rid of me”. Compared to his symphonies it is rather short, less than half an hour. Bruckner even contemplated using it as the last movement of his Ninth Symphony when he realized that he would not be able to complete a purely instrumental finale before his death.

Karajan conducted the “Te Deum” throughout his career (i.e. for almost 50 years) with soloists like Leontyne Price, Fritz Wunderlich, Nicolai Gedda, José van Dam and Agnes Baltsa.

— P.R. Jenkins